The novel kicks off with a reunion between friends known as the Mouse, Moll Byblow, Madam Lily de Luxe and Zelle, reminiscing about their days living in a 'club' together in the 1920s, going through turbulent youthful events and trying to find work in the theatre. It's now over four decades later. But... Zelle is absent, as she has been at all their five-yearly reunions. But is the shabby old woman across the road, who reminds 'Mouse' (the otherwise unnamed narrator) 'of the crones said to have sat knitting round the guillotine during the Reign of Terror', actually Zelle? And, if so, has she donned a disguise, or have 45 years apart led her to destitution?

And suddenly the novel flings us back those 45 years, to Mouse leaving her aunt's house and arriving in London, at that club. We see her first experiences through the lens of her journal, which feels like we're in familiar I Capture the Castle territory...

I am here at last! I arrived this afternoon, at Marylebone Station so I only had a short taxi drive - I wished it could have been longer as it was thrilling to be driving through London on my own. And it was such a lovely day. The trees here are further out than they are at home. Home! I haven't one any more. That thought doesn't make me feel sad. It makes me feel wonderfully free.Mouse, despite her nickname, isn't particularly timid, and isn't all that different from Cassandra of Smith's more famous novel. Both are young and inexperienced, but oddly confident and more worldly than they seem. Both are incredibly introspective, yet manage not to be annoyingly so - although Mouse gets rather closer to 'annoying' than Cassandra does. But while Cassandra is isolated in a highly romanticised setting in rural Suffolk, Mouse is flung into the maelstrom of the theatre. Oh, and the journal fades away after a few pages - being replaced with first-person narrative (so she is hardly ever called 'Mouse' in the book) but from the distance of 45 years.

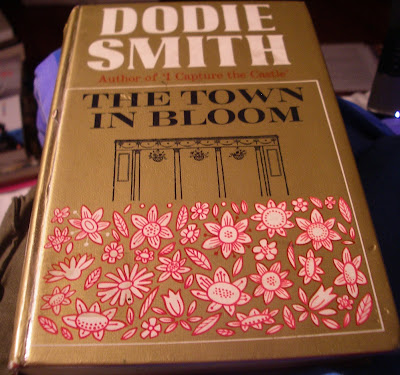

I love books about the theatre, fact or fiction, especially if it's about theatre of the 1920s or 1930s. So I lapped up the first half of The Town in Bloom - which is set in a theatre run by actor-manager Rex Crossway, last in a line of theatrical Crossways. Dodie Smith was herself both an actress and playwright (it was as pseudonymous playwright C. L. Anthony that she first found fame) so she writes this section in an informed and entertaining manner. Mouse launches herself into his world through an impromptu audition for The School for Scandal, playing both Sir Peter and Lady Teazle.

I played both of them. First, as Sir Peter, I looked to my right and used a deep, rich voice. Then, looking left, I became Lazy Teazle and used a lighter voice than was natural to me. Backwards and forwards from right to left I went, speaking fast because I feared Mr. Crossway would stop me. I particularly wanted to reach what was, for me, the high moment of the scene, when Sir Peter tells Lady Teazle she had no taste when she married him. Lady T. then goes into fits of laughter - that is, she did in my interpretation. And never had I laughed better, louder or longer than I did for Mr. Crossway. I checked my laughter with some very amusing gasps and continued the scene. Still Mr. Crossway did not interrupt me. So I went on until Lady Teazle's exit when I sketched a pert curtsy to Sir Peter - and then made a very deep one to Mr. Crossway.It was a brave, and a delicious, decision on Dodie Smith's part to make Mouse no prodigy - she is an appalling actress, and no amount of advice from Crossway can make her anything else. So, instead, she starts working in one of the theatre offices with Eve Lester, a kind, sensible, and wise woman in an environment of those who are often kind, but rarely the rest.

The backstage goings-on of a theatre fascinate me, and I loved all the minutiae of rehearsals, editing, understudies etc. - and a very amusing scene where Mouse takes it upon herself to replace the ill leading lady halfway through a play, completely changing the interpretation, and rather ruining the whole affair. All written rather cleverly, and Mouse's combination of naivety and knowingness make for a fun read.

But then...

Yes, Mouse falls in love with Mr. Crossway. Of course she does. At which point The Town in Bloom becomes significantly less interesting, while she repeatedly tries to seduce Mr. Crossway into an affair. I know there are plenty of real life relationships with big age gaps which work well, but I find them almost universally disturbing in novels - even up to and including Emma and Mr. Knightley. This is the sort of affair where Mr. Crossway laughingly calls her 'my dear' a lot, and she pontificates on how she will never love anybody else, not as long as she lives. And so on and so forth.

There are a few more twists to the tale, and her flatmates do play more significant roles than this review suggests, but I'm afraid The Town in Bloom turned into a rather tedious novel. There is enough momentum from the first half - and the lingering question from the prologue of what happened to Zelle - but the re-focus upon a rather tawdry romantic storyline is significantly duller than the theatrical focus of the earlier section to the novel.

In this respect, as in several others, The Town in Bloom is something of a pale shadow of I Capture the Castle, and I can quite see why nobody has bothered to reprint it for a while. I wish Smith had had the courage to leave out the romance/affair/adultery storyline altogether - this would have been an infinitely better novel without it, and would also have been rather further away from I Capture the Castle territory, and thus easier to appraise on its merits, not judged on its comparative demerits.

And not a dalmatian in sight.